Biography

I was brought up in the Yorkshire Dales, went to The Mount School, York, then to St Anne’s College, Oxford, where I read History. I taught History for three years, when I left to marry Richard Tuckwell, a nomadic Civil Engineer. Soon, via the Isle of Sheppey and the Mersey Estuary, we were sent to Guyana, part then of the British West Indies.

I did some part-time teaching and also wrote book reviews for the local paper. Sometimes it was suggested to me that I might write about the place itself, but that never appealed to me. It was only when we had been back home for over a year and people would ask me about life in Guyana, that I began to realise that the memory of it was getting blurred and I needed to try to set it down exactly as it was, with all the surprise of it, of the heat, of the contrasts between ancient and modern, of the moral confusion as missionaries in the bush tried to teach Amerindians, who shared everything, that there was such a thing as possession and to take someone else’s possession was a sin but never mind you could be converted to Christianity and your sins would be forgiven.

All these things had been astonishing at the time, but surprise is a fleeting quality, you get used to things. I wanted to recapture it exactly as it was.

It wasn’t a very convenient time to feel obliged to do this because by then I had a baby and a bit and by the time I finished the manuscript I had two babies. Clearly I couldn’t work during the day but it so happened that Richard had to work away from home from Monday to Friday, so the writing could be done at night.

It wasn’t a very convenient time to feel obliged to do this because by then I had a baby and a bit and by the time I finished the manuscript I had two babies. Clearly I couldn’t work during the day but it so happened that Richard had to work away from home from Monday to Friday, so the writing could be done at night.

I made the interesting discovery that at the end of a day of looking after babies you are physically exhausted and emotionally drained, but you haven’t actually taxed your brain at all. I could, at about seven o’clock and after plenty of coffee, settle down to work at my desk until at about midnight or – if I was lucky – two o’clock in the morning – I heard the first plaintive cry from upstairs.

I learned from that experience that you don’t find time for writing; you have to make it. I also learned my first lesson about publishers. I sent the first few chapters to a publisher who used to send me books for review in Guyana and received a very encouraging reply, urging me to finish it. But, when I did, I had an apologetic letter saying that they still liked it but the sales side said they didn’t know what category to put it in to sell it. Was it travel, or autobiography or humour? Travel books in those days weren’t supposed to be funny or too personal. It didn’t fit into any genre. I had roughly the same answer from other publishers; there seemed to be some kind of warfare between the literary side and the sales side.

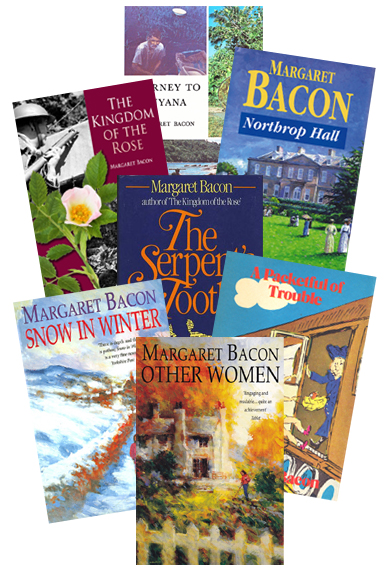

The last publisher I tried was Dennis Dobson, a small but very literary and somewhat idiosyncratic firm. The parcel came back just as we were making one of our many moves, this time to Cornwall, so I put it in a desk drawer and off it went in the furniture van. It remained unopened for several months when, needing some brown paper and remembering that, whatever their other failings, publishers had always returned my manuscripts in up-market brown paper, I unwrapped it. A letter fell out, saying that Dobsons had liked my book very much and would be proud to have it on their list. Dismayed, I assumed that after this long delay they would have given up on me, but they were very forgiving and published the book as Journey in Guyana in 1970.

At the time young writers were often advised by publishers to “study the market” and write accordingly. Maybe it worked for some, but I knew I could never write like that. When Dobsons asked me if I might write another travel book, I told them apologetically, that I’d started on a novel. I expected disapproval, but the reply was, “Always write what it is in you to write. Never be told what to write.” I think I was very lucky to have found a publisher who suited me so well. After Dennis Dobson died, while still a relatively young man, and they ceased publishing, I always kept in touch with the family.

All my other books have been novels. Richard’s work finally took us to Wiltshire where I still live, a widow now with two grandchildren.