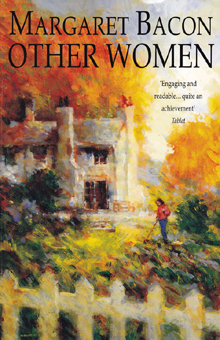

Other Women

Description

When successful business man, Grover Blackford falls to his death from the mountain fortress of Sigiria in Sri Lanka, it could have been a tragic accident.

On the other hand none of the people with him had reason to regret his passing. Indeed the world seemed a safer and sweeter place without him.

As the story unfolds the truth is finally revealed, but “Other Women” is more than a whodunit. It explores with sympathy, but also with sharp satirical humour, the shifting sands of family life as children grow up and parents move into middle age.

Corinne, Grover’s widow, has always seen herself in relation to a man: as a daughter, then a wife and now a widow. Not so her rebellious teenage daughter, Priscilla, who is very much a person in her own right. It is her influence which enables her mother, in a kind of role reversal, to assert her own independence.

Becky, the headmaster’s gentle and caring wife, also has a daughter who, born in a feminist era, cannot understand the ways of the previous generation. She is shocked that her parents had not lived together before marrying. “You wouldn’t go out and commit yourself to a computer without testing it, would you?” she points out. “But you committed yourself to a man for the rest of your life without even trying him out.” Later Becky finds herself wondering, “Who would have thought, in that far off time, that one day all that virtuous restraint would have to be apologised for?”

She too, after much suffering and emotional turmoil, finds the courage to reject responsibility for the action of others and forge a new life for herself, as they both discover that supported by other women they can work out their own salvation.

Europe and soon the outbreak of “the war to end all wars” will turn their world upside down, destroying all their old certainties.

Reviews

Grover Blackford dies in an apparent accident while walking on the rock of Sigiria in Sri Lanka. Not many mourn a man whose morals were dictated by expediency. Certainly not his dutiful and once loving wife who had to endure his affairs, and who now welcomes the opportunity to reclaim something of her own person. Not that Grover’s undoing comes from that quarter; no, this sprang from the damage wrought on a more defenceless person. With perception and wit – if at times frustration (“women do have a disturbing tendency to go on loving bastards”) Margaret Bacon examines the prisons women construct around themselves when they fall in love.

Daily Telegraph

One sentence sticks in the mind after reading this little gem of a novel. “Considering that he never read anything except the financial columns, pornographic magazines and the lessons in church on Sunday,” Grover’s widow said, “he really did have a remarkable weakness for literary ladies.”

A mere 32 words and Margaret Bacon has penned a memorable description of a critical character. Other Women succeeds on two levels. First as a whodunit; none of the four people present when Grover fell to his death abroad had reason to regret his passing. Secondly as a sharply observed psychological study about changing relationships between mother and daughter; husband and wife; husband and mistress.

Yorkshire Evening Press

A small steely gem of an account of the way in which the fine mechanisms of married life corrode…Bacon’s writing is a precision instrument with a sharp, satirical edge.

Sunday Telegraph

Other Women takes a wry and recognisable look at the shifting sand of family life and human relationships…highly entertaining

The Lady

Many years ago I remember Margaret Bacon saying she tried to reveal her characters little by little as though peeling off the layers of an onion.

Other Women is a triumphant example of this technique. We gradually get to understand Corinne Blackford and her late husband, the overbearing Grover, Becky Portman and the compliant, ineffectual Matthew.

By the end of the book, when one of them is revealed as Grover’s killer, we find ourselves hoping that the murderer will now live happily ever after.

For live on in the readers’ minds, these people surely will, particularly the women who realise (as their daughters, born in a feminist era, never will) that their whole experience has been second-hand.

“I was never somebody in my own right, I always existed in relation to somebody else,” Corinne suddenly thinks. But it’s not too late. She discovers there is a better life, alone, free and no longer young. The combination of sharp observation, sympathetic understanding and flashes of comedy make this as fine a novel as Margaret Bacon’s excellent earlier books.

Western Morning News

The deplorable Grover Blackford, embodiment of the thrusting business ethos of the Eighties and aptly described by his widow as “sixteen stone of solid selfishness” falls to his death from a mountain top in Sri Lanka. Or was he pushed?

At its beginning and end, Margaret Bacon’s novel includes elements of the Rendell or James type of whodunit, where exploration of the psyche predominates. In between, it traces Grover’s devastating impact on two women, his wife and his mistress, and their eventual recovery from emotional injury to the point where they become not just friends, but professional partners. The theme of the widow reclaiming her identity may not be new but it is enjoyably worked out; the account of the fastidious Becky’s anguished problems with adultery is delicate and touching. Particularly accurate is the common feminine amazement at the practised philanderer’s disregard for other people’s feelings. His last mistress’s tart remarks on Grover’s sexual prowess are a joy.

The Tablet